|

This week, kids and teens are invited to contribute creative protest signs to our Martin Luther King Jr “I Have a Dream” Protest Art Installation. With the goal of giving youth the opportunity to express their thoughts, feelings, and commitments to racial justice, artwork will be mounted on yard signs and installed on the library’s front lawn on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, January 18th. Completed protest art must be dropped off in the library lobby during our service hours no later than 4PM, Sunday, January 17th. Creative signs created by demonstrators at protests come in a wide variety of forms and formats. Some protesters create incredible, eye-grabbing visual art related to their cause. Others use humor, pop culture, impactful quotes, or clever words to pull observers in. Protest signs sharing simple but stark statistics are also used to provide evidence supporting the protesters’ cause in a concrete way. Throughout history, artists have also used shocking images and language to demand attention to important causes. While this activity and call for art is geared towards students of all ages, parents of younger children are encouraged to preview the blog post below and decide what is appropriate for their child. There is no right or wrong way to create protest art. The most important thing is that your message be heartfelt, honest, and clear. You can create your own unique design, or attach and complete any of the prompts included with your supplies. Please only use one side of your paper so it can be mounted for display. It can be tough to know where to start when discussing social justice and racism with younger kids. For help with starting the conversation, check out these children’s books relating to race and social justice, recommended by our Children’s Librarian and Assistant Director, Caroline Cares. Nonfiction:

Picture books:

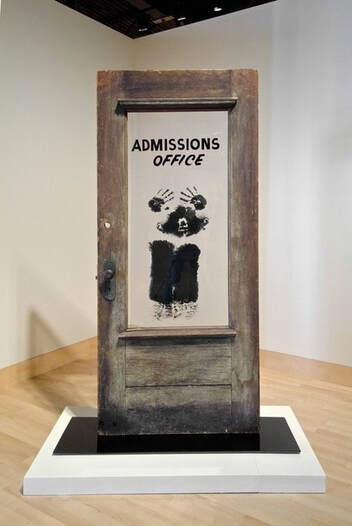

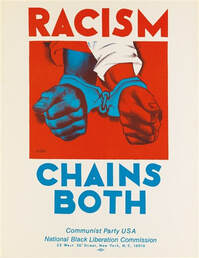

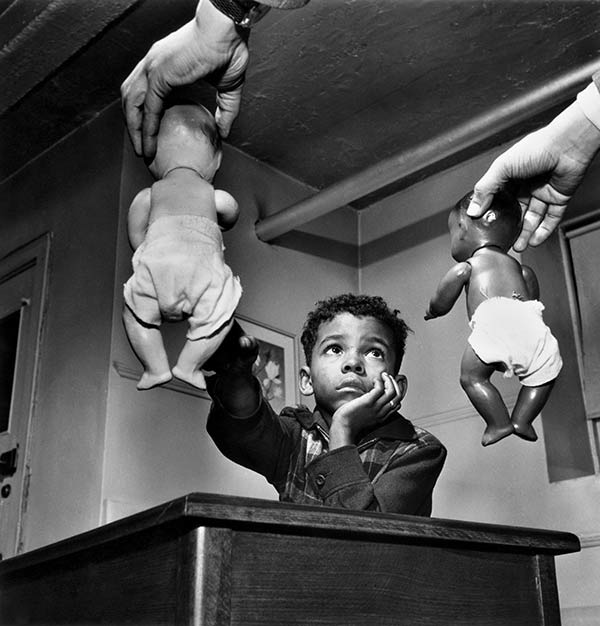

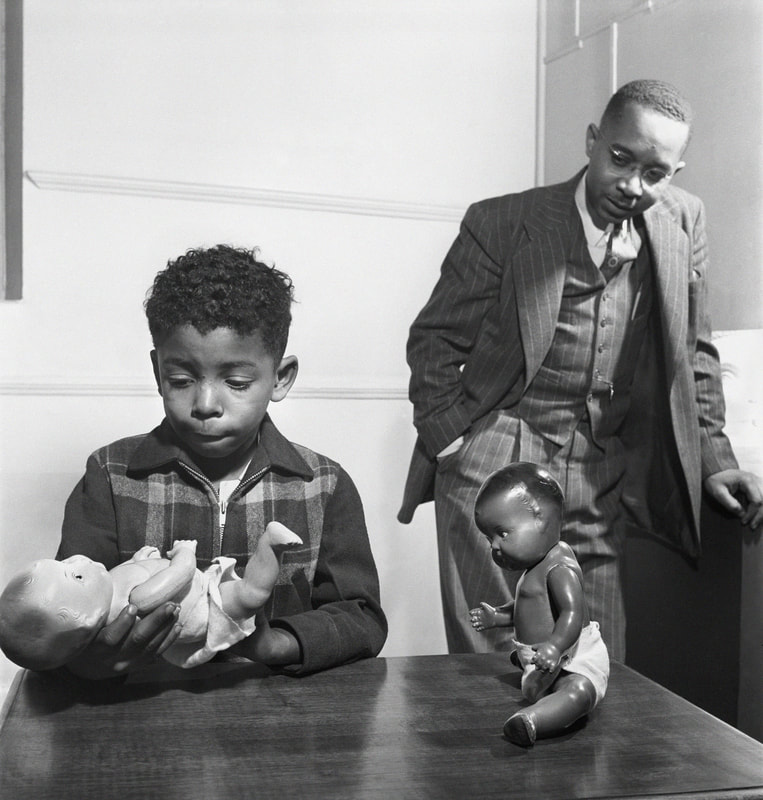

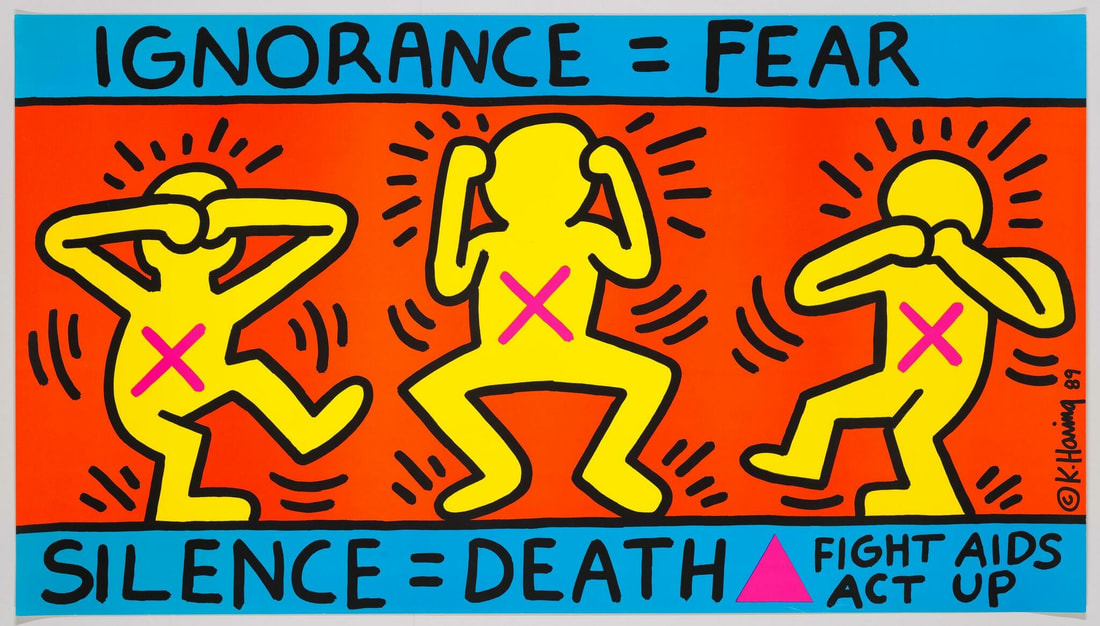

I Have a Dream - Illuminating the Truth and Illustrating the Possible A History of Art as Protest by ArtistYear Teaching Artist, Leila Milanfar. “We all know that art is not the truth. Art is the lie that makes us realize the truth.” — Pablo Picasso, painter of the anti-war mural entitled Guernica “I am invested in illustrating the possible.” — Theaster Gates, visual artist for social change and professor at the University of Chicago Illuminating the truth and illustrating the possible. This has been the work of millions of protest artists over thousands of years. Today, we honor one such individual, well-known for using expression to fight oppression. On August 28th, 1963, famous artist and activist Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic speech, I Have A Dream, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. You may be thinking, “MLK Jr.? An artist? But, he didn’t paint!” Perhaps not… but, MLK did center his life around ‘illustrating the possible’ through his powerfully performed speeches. We all remember the first time we heard his booming voice proclaim: “I have a dream… that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” MLK Jr. illuminated a future that racism obscured. He used his words and his voice to paint the picture of a newly vibrant and compassionate Southern world; one without Jim Crow segregation. One where “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” And think about it: MLK stood in front of 250,000 people when he told this story. That’s a type of crowd most Broadway stars only dream of! Literary art and speech-giving are impactful art forms — ones that Martin Luther King Jr. mastered and used to the advantage of the nation. Martin Luther King Jr.’s creative legacy runs parallel to that of so many other brilliant leaders and artists. Let’s take a quick walk through history and explore some more protest art! Art that Illuminates the truth Strange Fruit. Recorded by Billie Holiday. Written by Abel Meeropol. (1939) Southern trees bear a strange fruit Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black bodies swingin' in the Southern breeze Strange fruit hangin' from the poplar trees Pastoral scene of the gallant South The bulgin' eyes and the twisted mouth Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh Then the sudden smell of burnin' flesh Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck For the rain to gather For the wind to suck For the sun to rot For the tree to drop Here is a strange and bitter crop Second-generation Russian-Jewish immigrant, English teacher and poet, Abel Meeropol, wrote Strange Fruit in 1939 after seeing a photograph of a Black man being lynched in the South. Lynching was a practice in which white community members in a certain town would forcibly hang Black people from trees by their necks, in order to kill them. Though the song never mentions lynching specifically, it is clear that Meeropol is describing that haunting photo of a body hanging from a tree. Later recorded by iconic Harlem Renaissance singer Billie Holiday, the song serves as a painful reminder of the violence that Black people faced everywhere. See Billie Holiday perform the piece here: https://youtu.be/-DGY9HvChXk Abel Meeropol is a wonderful example of allyship, in that he powerfully expressed his discontent with oppression in a song and then gave ownership of that song to a Black musician. Interestingly, as an English teacher in the Bronx, Meeropol taught James Baldwin, who would end up becoming a famous author and civil rights activist himself. Science and art change the nation. In the 1940s, Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark conducted the “Doll Test” to measure the effects of segregation on Black youth. In the experiment, Drs. Clark showed Black children two dolls, a Black doll and a white doll. They then asked the children to point to the “nice doll.” Nearly all the Black children pointed to the white doll. Next, he asked which doll they would like to play with. Again, nearly all the Black children chose the white doll. Finally, Drs. Clark asked, “Which doll is most like you?” The Black children indicated the Black doll, thus demonstrating internalized racism. This self-deprecation was later found to be associated with the erroneous “separate but equal” assertion that fueled segregation. Gordon Parks’ images of this vulnerable young boy unsettled those who had not considered the long term repercussions of Jim Crow. This protest photography coupled with the peer-reviewed, scientific paper written by the Clarks were later cited in the Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision to end segregation of schools. Clark Doll Experiment in Harlem, New York. Photograph by Gordon Parks (1947)  Strength among hate. In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision resulted in the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Nine Black students, including Elizabeth Eckford pictured here at 15 years old, enrolled in the high school. As these nine Black students tried to walk into the school building on their first day, white students and community members followed and berated them. The mob’s expression of hatred and contempt, captured and circulated by photographer Will Counts, showed the ugly, but human, side of racism in the South. Images such as these served as kindling for the Civil Rights Movement. Elizabeth Eckford of the Little Rock Nine. Little Rock, Arkansas. Photograph by Will Counts (1954).  Knock or break the glass? The Door is a simple, yet powerful installation symbolizing the barriers to success facing Black Americans. Despite the desegregation of most universities following Brown v. Board of Education, Black students still had a harder time gaining admission in comparison to their white counterparts. This difficulty arose both from prejudice among admissions officers and institutional disadvantages like poorly funded high schools in Black neighborhoods and limited access to admissions counseling. To create this piece, David Hammons coated parts of his own body with black paint and then pressed himself onto the glass door. This action, which resulted in the piece itself, mirrored the plight of Black students. Through the glass of the Admissions Door, these students saw the future of their education, but the door itself was locked. The only feasible solution was to lean on the door to try and force it open. This effort, however, seems to be in vain. The handle is still locked and their pushing requires Black students to leave something of themselves behind — much like Hammons’ desperate hand prints pressed onto the cold glass of The Door. This futility calls back to a quote from Martin Luther King Jr’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” which reads, “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor, it must be demanded by the oppressed.” The Door (Admissions Office). Installation by David Hammons (1969).  Three Words on Allyship. An avid member of the Communist Party of American, Hugo Gellert painted this poster around 1970 in collaboration with the National Black Liberation Commission. An early 1900s immigrant from Hungary, Gellert used his art to illustrate the racial and financial inequality he witnessed in New York. This poster is both self-explanatory and profound, again calling back to a quote from MLK Jr’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. King says, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Gellert’s allyship to the Civil Rights Movement serves as inspiration to those of us that may not be a part of an oppressed community, but seek to champion justice for all. Immorality towards any one group is an issue we all must face to overcome. Racism Chains Both. Poster art by Hugo Gellert (c. 1970). Provocative murals take over NYC streets. Keith Haring, a 1980s pop-graffiti artist, advocated for HIV/AIDS awareness, the end of South African apartheid, and the cessation of crack use among New Yorkers. Although he died of HIV at age 31, his work solidified the importance of creative, public discussion of taboo topics, as well as allyship. A member of the LGBTQ+ community, Haring advocated for the rights of his peers as well as the Black community in the United States and overseas. Much like the style of Hugo Gellert (above) Haring’s style also inspires many of the contemporary protest signs we see at protests today.  We Demand. In 1963, protesters marched on Washington holding posters that donned variations of the phrase “We Demand Equal Rights Now!” Though protest posters had existed since the abolition days, the March on Washington popularized the modern poster design. Catchy, simple slogans prevailed, as opposed to the detailed nature of 1910s women’s suffrage posters. It is unknown who designed the We Demand posters, but they mirrored the persuasive urgency and frankness of wartime propaganda and proved just as effective. This design was the first mass produced Civil Rights poster and inspired countless others, like the National Organization for Women’s ‘Keep Abortion Legal’ posters and contemporary ‘Black Lives Matter’ posters. March on Washington 1963. Photo from Equal Justice Initiative.  When You Grow Up. In the 1970s, painter Faith Ringgold visited the Rikers Island Correctional Institution for Women, also known as the Women’s House of Detention, and spoke with the incarcerated. The Women’s House notoriously held Angela Davis and other revolutionaries during the Civil Rights Movement and its aftermath. After the inmate interviews, Ringgold created this mural — an amalgamation of the women’s wishes for a future of equality. Installed in the prison for all to see, Ringgold’s mural paints a picture of a world where women from all walks of life could achieve anything they set their minds to, from playing on the New York Knicks to becoming a doctor. This piece is a perfect example of art’s power to illustrate the possible. Although the inmates could not live the futures they wanted, they could imagine them, and Ringgold’s paint brush could bring them to life. For The Women’s House. Painting by Faith Ringgold (1972) Still I Rise BY MAYA ANGELOU You may write me down in history With your bitter, twisted lies, You may trod me in the very dirt But still, like dust, I'll rise. Does my sassiness upset you? Why are you beset with gloom? ’Cause I walk like I've got oil wells Pumping in my living room. Just like moons and like suns, With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high, Still I'll rise. Did you want to see me broken? Bowed head and lowered eyes? Shoulders falling down like teardrops, Weakened by my soulful cries? Does my haughtiness offend you? Don't you take it awful hard ’Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines Diggin’ in my own backyard. You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I’ll rise. Does my sexiness upset you? Does it come as a surprise That I dance like I've got diamonds At the meeting of my thighs? Out of the huts of history’s shame I rise Up from a past that’s rooted in pain I rise I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide, Welling and swelling I bear in the tide. Leaving behind nights of terror and fear I rise Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear I rise Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise I rise I rise. Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise” is an energetic and mighty exclamation of self-worth and confidence in the face of oppression. Angelou describes the injustices of her oppressor with attitude and sass, casting away their attempts to beat her down with the promise, “still, I rise.” For the full effect of her energy, see her perform the poem live here: https://youtu.be/qviM_GnJbOM The infectious spirit of this work has inspired many, including Nelson Mandela, who recited the poem at his 1994 inauguration after serving 27 years in prison. Still I Rise. Poem by Maya Angelou (1978)  In April 2016, protesters began camping in the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota to demand the cessation of construction on the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline construction would flow directly through sacred Native territory, without permission, and residents say that one leak could pollute tons of essential water. Police and other law enforcement brutalized these unarmed water protectors, leading to nationwide protests and discontent. Charles Rencountre, a Lakota artist who grew up in South Dakota, and his wife Alicia Marie Rencountre-Da Silva decided that a copy of their “Not Afraid to Look” sculpture, a piece previously on display at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, needed to sit at Standing Rock. The name “Not Afraid To Look” is a callback to a mid-19th century Lakota pipe design called “Not Afraid To Look a White Man in the Face.” As the sculpture sits facing the protests, it reminds all to push aside fear of the oppressor and fight for justice. See more Native protest are in the Museum of Vancouver’s Virtual Indigenous Protest Art Exhibit called “Acts of Resistance” linked here: https://museumofvancouver.ca/acts-of-resistance Not Afraid to Look. Sculpture by Lower Brule Sioux artist Charles Rencountre and Alicia Marie Rencountre-Da Silva (2016)  We live in a world more divided than ever, but also more expressive than ever. In 2020, we saw the second rise of the Black Lives Matter movement amid a global pandemic and widespread unity against racism in all forms. This mural, painted in Oakland, California, serves as an homage to all those who have supported one another in the fight for justice. Each hand in this mural represents a person of a different culture and the three words emblazoned above these hands read “WE GOT US.” Below the mural, is a small altar of ancestral remembrance. When we work together and support one another, change is more than possible — it’s inevitable! We Got Us. Mural by Cece Carpio, Nisha Kaur Sethi, Priya Handa, and Trust Your Struggle Collective. Oakland, California (June 2020) What a ride! And, to think, all the art you just explored is only a drop in the ocean of art history online! All the way back in 1517, Martin Luther vandalized a Catholic Church by nailing his 95 Theses to the door, and thus began Protestantism. In the twentieth century, Martin Luther King Jr. and many others invigorated the nation and demanded morality with their own creative expression. Now, the next chapter of protest art is in your hands! Sources: MLK “I Have A Dream” Speech, In Its Entirety https://www.npr.org/2010/01/18/122701268/i-have-a-dream-speech-in-its-entirety The Strange Story Of The Man Behind ‘Strange Fruit’ https://www.npr.org/2012/09/05/158933012/the-strange-story-of-the-man-behind-strange-fruit Abel Meeropol https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abel_Meeropol Racial Innocence in Postwar America https://aperture.org/editorial/racial-innocence-postwar-america/ How an Experiment With Dolls Helped Lead to School Integration https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/07/upshot/how-an-experiment-with-dolls-helped-lead-to-school-integration.html Will Counts: The Central High School Photographs https://www.arkansasartscenter.org/will-counts-the-central-high-school-photographs From the Archives: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties at the Brooklyn Museum https://www.dailyserving.com/2014/12/from-the-archives-witness-art-and-civil-rights-in-the-sixties-at-the-brooklyn-museum/ https://d1lfxha3ugu3d4.cloudfront.net/education/docs/Witness_Teacher_Packet.pdf Library of Congress Racism Chains Both/ Hugo Gellert https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3g10803/ Keith Haring https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keith_Haring From the Archive, 29 August 1963: 200,000 demonstrate for Civil Rights https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2011/aug/29/archive-200000-demonstrate-for-civil-rights-1963 The Long 19th Amendment: Suffrage Posters https://long19.radcliffe.harvard.edu/projects/exhibit_seeingcitizens/section_3/sub_1/ Library of Congress World War II Posters https://www.loc.gov/item/2003542663/ Hyperallergic article An Exhibition About Revolution that Keeps Faith with Ringgold https://hyperallergic.com/399211/keeping-faith-with-ringgold/ “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46446/still-i-rise Analysis of “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou https://owlcation.com/humanities/Analysis-Of-Still-I-Rise-By-Maya-Angelou NRDC A Statue at Standing Rock Sends a Powerful Message of Resistance. https://www.nrdc.org/onearth/statue-standing-rock-sends-powerful-message-resistance The Best Bay Area Murals in 2020: Oakland’s Sprawling “Black Lives Matter” https://www.nrdc.org/onearth/statue-standing-rock-sends-powerful-message-resistance "TENGO UN SUEÑO" INSTALACIÓN DE ARTE DE PROTESTA Se invita a los niños y adolescentes a expresar sus pensamientos, sentimientos y compromisos a la justicia racial creando señales de arte de protesta para el “Yo tengo un sueño”: Instalación De Arte De Protesta de la Biblioteca Regional de Basalt. El arte debe ser creado o colocado en signos de 18" x 24" proporcionados por la biblioteca. Entregue su arte para el Domingo 17 de Enero. Los carteles creativos creados por los manifestantes en las protestas vienen en una amplia variedad de formas y formatos. Algunos manifestantes crean arte visual increíble y llamativo relacionado con su causa. Otros utilizan el humor, la cultura pop, citas impactantes o palabras ingeniosas para atraer a los observadores. Los carteles de protesta que comparten estadísticas simples pero crudas también se utilizan para proporcionar evidencia que respalde la causa de los manifestantes de manera concreta. A lo largo de la historia, los artistas también han utilizado imágenes y lenguaje impactantes para exigir atención a causas importantes. Si bien esta actividad y convocatoria de arte está dirigida a estudiantes de todas las edades, se anima a los padres de niños más pequeños a que vean la publicación del blog a continuación y decidan qué es apropiado para su hijo. No existe una forma correcta o incorrecta de crear arte de protesta. Lo más importante es que su mensaje sea sincero, honesto y claro. Puede crear su propio diseño único o adjuntar y completar cualquiera de las indicaciones incluidas con sus suministros. Utilice solo una cara del papel para que pueda montarse para su visualización. Puede ser difícil saber por dónde empezar cuando se habla de justicia social y racismo con niños más pequeños. Si necesita ayuda para iniciar la conversación, consulte estos libros para niños relacionados con la raza y la justicia social, recomendados por nuestra bibliotecaria infantil y subdirectora, Caroline Cares. Libros de No ficción:

Libros Ilustrados:

"TENGO UN SUEÑO" - Todos sabemos que el arte no es la verdad Una Historia del arte como forma de protesta por Leila Milenfar “Todos sabemos que el arte no es la verdad. El arte es la mentira que nos hace darnos cuenta de la verdad.” - Pablo Picasso, pintor del mural pacifista titulado Guernica “Estoy comprometido en ilustrar lo posible”. - Theaster Gates, artista visual para el cambio social y profesor de la Universidad de Chicago Iluminando la verdad e ilustrando lo posible. Este ha sido el trabajo de millones de artistas de protesta durante miles de años. Hoy, honramos a una de esas personas, conocida por usar la expresión para combatir la opresión. El 28 de agosto de 1963, el famoso artista y activista Martin Luther King Jr. pronunció su icónico discurso, Tengo Un Sueño, en los escalones del Monumento de Lincoln. Quizás estás pensando, “¿MLK Jr.? ¿Un artista? ¡Pero no pintó! " La verdad es que no ... pero MLK centró su vida en "ilustrar lo posible" a través de sus poderosos discursos. Todos recordamos la primera vez que escuchamos su voz retumbante proclamar: "Tengo un sueño ... que mis cuatro hijos pequeños algún día vivirán en una nación donde no serán juzgados por el color de su piel sino por el contenido de su carácter.” MLK Jr. iluminaba un futuro que el racismo oscurecía. Usaba sus palabras y su voz para pintar la imagen de un nuevo mundo del sur vibrante y compasivo; uno sin segregación Jim Crow. Uno donde "los niños negros y las niñas negras podrán unirse a los niños blancos y las niñas blancas como hermanas y hermanos.” Y piénselo: MLK se paró frente a 250.000 personas mientras contaba esta historia. ¡Ese es el tipo de público con el que solo sueñan las estrellas de Broadway! El arte literario y los discursos son formas de arte importantes — unas que Martin Luther King Jr. dominó de joven y utilizaba continuamente para el beneficio de la nación. *** A lo largo de la historia, los artistas han utilizado imágenes y lenguaje que otros consideran espantosos o profanos para llamar la atención sobre temas importantes. Si bien esta actividad y convocatoria para el arte está dirigida a estudiantes de todas las edades, recomendamos a los padres de niños más pequeños que vean el arte en este blog y luego decidan qué es apropiado para su hijo. Puede ser difícil saber por dónde empezar cuando se habla de justicia social y racismo con niños más pequeños. Si necesita ayuda para iniciar la conversación, consulte estos libros para niños sobre la raza y la justicia social, recomendados por nuestra bibliotecaria infantil y directora, Caroline. *** El legado creativo de Martin Luther King Jr. es paralelo al de tantos otros líderes y artistas brillantes. ¡Hagamos un breve paseo por la historia y exploremos más arte de protesta! Arte que ilumina la verdad Strange Fruit. Grabado por Billie Holiday. Escrito por Abel Meeropol. (1939) Los árboles del sur dan una fruta extraña Sangre en las hojas y sangre en la raíz Cuerpos negros balanceándose en la brisa del sur Fruta extraña colgando de los álamos Escena pastoral del sur galante Los ojos saltones y la boca torcida Aroma de magnolias dulce y fresco Entonces el repentino olor a carne quemada Aquí hay una fruta para que arranquen los cuervos Para que la lluvia se junte Para que el viento lo chupe Para que el sol se pudra Para que el árbol caiga Aquí hay una cosecha extraña y amarga El inmigrante ruso-judío de segunda generación, profesor de inglés y poeta, Abel Meeropol, escribió Strange Fruit en 1939 después de ver una fotografía de un hombre negro siendo linchado en el sur. El linchamiento era una práctica en la que los miembros blancos de una comunidad colgaban a la fuerza a los negros de los árboles por el cuello para matarlos. Aunque la canción nunca menciona el linchamiento específicamente, está claro que Meeropol describe esa foto inquietante de un cuerpo colgando de un árbol. Más tarde, grabada por la icónica cantante de Harlem Renaissance Billie Holiday, la canción sirve como un doloroso recordatorio de la violencia que enfrentan los negros en todas partes. Vea a Billie Holiday cantar la pieza aquí: https://youtu.be/-DGY9HvChXk Abel Meeropol es un ejemplo maravilloso de alianza. Expresó poderosamente su descontento con la opresión en una canción y luego le dio la propiedad de esa canción a una música negra. Curiosamente, como profesor de inglés en el Bronx, Meeropol enseñó a James Baldwin, quien terminaría convirtiéndose en un famoso autor y activista de los derechos civiles. La ciencia y el arte cambian la nación. En la década de 1940, el Dr. Kenneth Clark y el Dr. Mamie Clark llevaron a cabo la "Prueba de las muñecas" para medir los efectos de la segregación en los jóvenes negros. En el experimento, los Dres. Clark les mostró a los niños negros dos muñecos, un muñeco negro y un muñeco blanco. Luego les pidieron a los niños que señalaran la "linda muñeca". Casi todos los niños negros señalaron la muñeca blanca. A continuación, preguntó con qué muñeca les gustaría jugar. Nuevamente, casi todos los niños negros eligieron la muñeca blanca. Finalmente, los Dres. Clark preguntó: "¿Qué muñeca se parece más a ti?" Los niños negros señalaron al muñeco negro, demostrando así un racismo interiorizado. Más tarde se descubrió que esta autodesprecio estaba asociada con la afirmación errónea de “separados pero iguales” que alimentaba la segregación. Las imágenes de Gordon Parks de este joven vulnerable inquietaron a quienes no habían considerado las repercusiones a largo plazo de Jim Crow. Esta fotografía de protesta, junto con el artículo científico revisado por pares, escrito por los Clarks, fue citado más tarde en la decisión de la Corte Suprema Brown contra la Junta de Educación de poner fin a la segregación de escuelas. Experimento de Clark Doll en Harlem, Nueva York. Fotografía de Gordon Parks (1947) Fuerza entre el odio. En 1954, la decisión de la Corte Suprema de Brown contra la Junta de Educación resultó en la eliminación de la segregación de Little Rock Central High School en Little Rock, Arkansas. Nueve estudiantes negros, incluida Elizabeth Eckford que se muestra aquí a los 15 años, se inscribieron en la escuela secundaria. Cuando estos nueve estudiantes negros intentaron entrar al edificio de la escuela en su primer día, los estudiantes blancos y miembros de la comunidad los siguieron y los reprendieron. La expresión de odio y desprecio de la mafia, capturada y difundida por el fotógrafo Will Counts, mostró el lado feo, pero humano, del racismo en el sur. Imágenes como estas sirvieron de encendido para el Movimiento de Derechos Civiles. Elizabeth Eckford de Little Rock Nine. Little Rock, Arkansas. Fotografía de Will Counts (1954). ¿Golpear o romper el cristal? The Door es una instalación simple pero poderosa que simboliza las barreras al éxito que enfrentan los afroamericanos. A pesar de la desagregación de la mayoría de las universidades después de Brown v. Board of Education, los estudiantes negros todavía tenían más dificultades para obtener la admisión en comparación con sus homólogos blancos. Esta dificultad surgió tanto del prejuicio entre los funcionarios de admisiones como de las desventajas institucionales, como las escuelas secundarias mal financiadas en los vecindarios negros y el acceso limitado a la consejería de admisiones. Para crear esta pieza, David Hammons cubrió partes de su propio cuerpo con pintura negra y luego se presionó contra la puerta de vidrio. Esta acción, que resultó en la pieza en sí, reflejó la difícil situación de los estudiantes negros. A través del cristal de la puerta de admisión, estos estudiantes vieron el futuro de su educación, pero la puerta en sí estaba cerrada. La única solución viable era apoyarse en la puerta para intentar abrirla a la fuerza. Sin embargo, este esfuerzo parece en vano. La manija todavía está cerrada y su empuje requiere que los estudiantes negros dejen algo de sí mismos atrás, al igual que las desesperadas huellas de las manos de Hammons presionadas en el frío vidrio de The Door. Esta futilidad nos recuerda una cita de la "Carta desde la cárcel de Birmingham" de Martin Luther King Jr de 1963 que dice: "Sabemos por experiencia dolorosa que la libertad nunca la otorga voluntariamente el opresor, sino que los oprimidos la deben exigir.” The Door (Oficina de Admisiones). Instalación de David Hammons (1969). Tres palabras sobre Allyship. Un miembro ávido del Partido Comunista de Estados Unidos, Hugo Gellert pintó este cartel alrededor de 1970 en colaboración con la Comisión Nacional de Liberación Negra. Gellert, un inmigrante húngaro de principios de la década de 1900, usó su arte para ilustrar la desigualdad racial y financiera que presenció en Nueva York. Este póster se explica por sí mismo y es profundo, y vuelve a recordar una cita de la carta de MLK Jr desde la cárcel de Birmingham. King dice: "La injusticia en cualquier lugar es una amenaza para la justicia en todas partes". La alianza de Gellert con el Movimiento por los Derechos Civiles sirve de inspiración para aquellos de nosotros que no somos parte de una comunidad oprimida, pero buscamos defender la justicia para todos. La inmoralidad hacia cualquier grupo es un problema que todos debemos enfrentar para superar. El racismo encadena a ambos. Póster de Hugo Gellert (c. 1970). Los murales provocativos se apoderan de las calles de Nueva York. Keith Haring, un artista de graffiti pop de la década de 1980, abogó por la concienciación sobre el VIH / SIDA, el fin del apartheid sudafricano y el cese del consumo de crack entre los neoyorquinos. Aunque murió de VIH a los 31 años, su trabajo consolidó la importancia de la discusión pública y creativa de temas tabú, así como la alianza. Un miembro de la comunidad LGBTQ +, Haring abogó por los derechos de sus compañeros, así como de la comunidad negra en los Estados Unidos y en el extranjero. Al igual que el estilo de Hugo Gellert (arriba), el estilo de Haring también inspira muchos de los carteles de protesta contemporáneos que vemos en las protestas de hoy. Arte que ilustra lo posible Nosotros demandamos. En 1963, los manifestantes marcharon en Washington con carteles que mostraban variaciones de la frase "¡Exigimos la igualdad de derechos ahora!" Aunque los carteles de protesta habían existido desde los días de la abolición, la Marcha sobre Washington popularizó el diseño de carteles modernos. Prevalecieron consignas pegadizas y sencillas, a diferencia de la naturaleza detallada de los carteles del sufragio femenino de la década de 1910. Se desconoce quién diseñó los carteles de We Demand, pero reflejaban la urgencia persuasiva y la franqueza de la propaganda bélica y demostraron ser igualmente efectivos. Este diseño fue el primer póster de derechos civiles producido en masa e inspiró a muchos otros, como los carteles "Mantener legal el aborto" de la Organización Nacional para la Mujer y los carteles contemporáneos "Black Lives Matter.” Marzo en Washington 1963. Foto de Equal Justice Initiative. En la década de 1970, la pintora Faith Ringgold visitó la Institución Correccional para Mujeres de Rikers Island, también conocida como la Casa de Detención de Mujeres, y habló con los encarcelados. La Casa de la Mujer detuvo notoriamente a Angela Davis y otros revolucionarios durante el Movimiento de Derechos Civiles y sus secuelas. Después de las entrevistas con las reclusas, Ringgold creó este mural, una amalgama de los deseos de las mujeres de un futuro de igualdad. Instalado en la prisión para que todos lo vean, el mural de Ringgold pinta una imagen de un mundo donde las mujeres de todos los ámbitos de la vida podrían lograr cualquier cosa que se propongan, desde jugar en los New York Knicks hasta convertirse en doctoras. Esta pieza es un ejemplo perfecto del poder del arte para ilustrar lo posible. Aunque los presos no podían vivir el futuro que querían, podían imaginarlos, y el pincel de Ringgold podía darles vida. Para la casa de la mujer. Pintura de Faith Ringgold (1972) Still I Rise Por MAYA ANGELOU Puedes escribirme en la historia Con tus amargas y retorcidas mentiras Puedes pisarme en la mismísima tierra Pero aún así, como polvo, me levantaré. ¿Mi descaro te molesta? ¿Por qué estás acosado por la tristeza? Porque camino como si tuviera pozos de petróleo Bombeo en mi sala de estar. Como lunas y como soles, Con la certeza de las mareas Al igual que las esperanzas brotando alto Aún así me levantaré. ¿Querías verme roto? ¿Cabeza inclinada y ojos bajos? Hombros cayendo como lágrimas ¿Debilitado por mis gritos conmovedores? Mi arrogancia te ha ofendido? No te lo tomes tan mal Porque me río como si tuviera minas de oro Cavando en mi propio patio trasero. Puedes dispararme con tus palabras Puedes cortarme con tus ojos Puedes matarme con tu odio Pero aún así, como el aire, me levantaré. ¿Te molesta mi sensualidad? ¿Viene como una sorpresa? Que bailo como si tuviera diamantes ¿En el encuentro de mis muslos? De las chozas de la vergüenza de la historia me levanto De un pasado arraigado en el dolor me levanto Soy un océano negro, saltando y ancho Inflamación e hinchazón que soporto en la marea. Dejando atrás noches de terror y miedo me levanto En un amanecer que es maravillosamente claro me levanto Trayendo los regalos que dieron mis antepasados, Soy el sueño y la esperanza del esclavo. me levanto me levanto Me levanto. "Still I Rise" de Maya Angelou es una enérgica y poderosa exclamación de autoestima y confianza frente a la opresión. Angelou describe las injusticias de su opresor con actitud y descaro, desechando sus intentos de golpearla con la promesa, "aún así, me levanto". Para ver el efecto completo de su energía, mírala interpretar el poema en vivo aquí: https://youtu.be/qviM_GnJbOM El espíritu contagioso de este trabajo ha inspirado a muchos, incluido Nelson Mandela, quien recitó el poema en su inauguración en 1994 después de cumplir 27 años. años de prisión. Todavía me levanto. Poema de Maya Angelou (1978)) En abril de 2016, los manifestantes comenzaron a acampar en la reserva de Standing Rock Sioux en Dakota del Norte para exigir el cese de la construcción del oleoducto Dakota Access. La construcción de la tubería fluiría directamente a través del territorio sagrado de los nativos, sin permiso, y los residentes dicen que una fuga podría contaminar toneladas de agua esencial. La policía y otras fuerzas del orden brutalizaron a estos protectores de agua desarmados, lo que provocó protestas y descontento en todo el país. Charles Rencountre, un artista lakota que creció en Dakota del Sur, y su esposa Alicia Marie Rencountre-Da Silva decidieron que una copia de su escultura "Not Afraid to Look", una pieza anteriormente expuesta en el Museo de Arte Nativo Contemporáneo de Santa Fe, Nuevo México, necesitaba sentarse en Standing Rock. El nombre "No tengo miedo de mirar" es una devolución de llamada a un diseño de tubería Lakota de mediados del siglo XIX llamado "No tengo miedo de mirar a un hombre blanco en la cara". Mientras la escultura se sienta frente a las protestas, recuerda a todos que deben dejar de lado el miedo al opresor y luchar por la justicia. Vea más Las protestas nativas están en la Exposición Virtual de Arte de Protesta Indígena del Museo de Vancouver llamada "Actos de Resistencia" vinculada aquí: https://museumofvancouver.ca/acts-of-resistance Sin miedo a mirar. Escultura del artista Charles Rencountre y Alicia Marie Rencountre-Da Silva del Lower Brule Sioux (2016) Vivimos en un mundo más dividido que nunca, pero también más expresivo que nunca. En 2020, vimos el segundo auge del movimiento Black Lives Matter en medio de una pandemia global y una unidad generalizada contra el racismo en todas sus formas. Este mural, pintado en Oakland, California, sirve como un homenaje a todos aquellos que se han apoyado mutuamente en la lucha por la justicia. Cada mano en este mural representa a una persona de una cultura diferente y las tres palabras estampadas sobre estas manos dicen "NOS CONSEGUIMOS". Debajo del mural, hay un pequeño altar de recuerdo ancestral. Cuando trabajamos juntos y nos apoyamos unos a otros, el cambio es más que posible, ¡es inevitable! Nos tenemos a nosotros. Mural de Cece Carpio, Nisha Kaur Sethi, Priya Handa y Trust Your Struggle Collective. Oakland, California (junio de 2020) ¡Qué viaje! Y, pensar, ¡todo el arte que acabas de explorar es solo una gota en el océano de la historia del arte en línea! En 1517, Martín Lutero destrozó una Iglesia católica clavando sus 95 tesis en la puerta, y así comenzó el protestantismo. En el siglo XX, Martin Luther King Jr. y muchos otros vigorizaron a la nación y exigieron moralidad con su propia expresión creativa. ¡Ahora, el próximo capítulo del arte de protesta está en tus manos!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Adult News & reviewsLibrary news, info about upcoming events, reviews of books and films, and a look at the topics that affect us as a library. Archives

July 2023

|

General |

Borrowing |

About |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed